This picture explains my entire journey to Canada to explore the options of expressing myself as a feminist and a woman. My quest for women's advocacy and women's rights got drowned by the patriarchy and male dominance of Nigerian society. I come from a country where women are not heard but seen, and their cries are neither heard nor attended to; instead, they keep quiet or face the consequence of being persistent. Men lead key political positions with masculine leadership concepts nurtured by culture and Nigeria's already existing political manly trajectory. For instance, the senatorial jobs in Nigeria are 109, and currently, there are only seven women in these positions, while the House of Representatives has 22 women out of the 320 members. There has never been a female president or governor in the entire history of Nigeria. The women that try to vie for political offices must have the support of their male partners while they act as puns in the hands of these male players. As mentioned, it affected my stay as a feminist as my life got threatened for advocating for basic fundamental human rights and being the voice for impoverished women.

It is in line with my first concept described by Mary Hawkesworth in the article "Engendering Political Science: An immodest proposal". The author described the difference between males and females in politics. The author explained that women legislators would prioritize issues such as women's rights, education, health care, families, children, and the environment and are willing to devote effort to securing the passage of progressive legislation in these areas. I decided to get equipped with the knowledge and find a safe place to be a feminist and find ways of transnational movements to my country without being prejudiced. I decided to leave Nigeria.

The multicultural policies and the diversity in Canada endeared me to look at avenues for studying and perhaps become a permanent resident and a citizen in the future. Immigration policies in Canada have opened up various opportunities for migration. The option of coming as an economic migrant will involve showing the finance available for yourself and your immediate dependents. The second option is coming in as a live-in caregiver that would require funding from the client that needs the review of the client before a favourable response will come from the IRCC. The first option was not possible for me as a Nigerian woman due to the funds involved, and the second option I felt will still place me in a subjugate situation that I intend to escape.

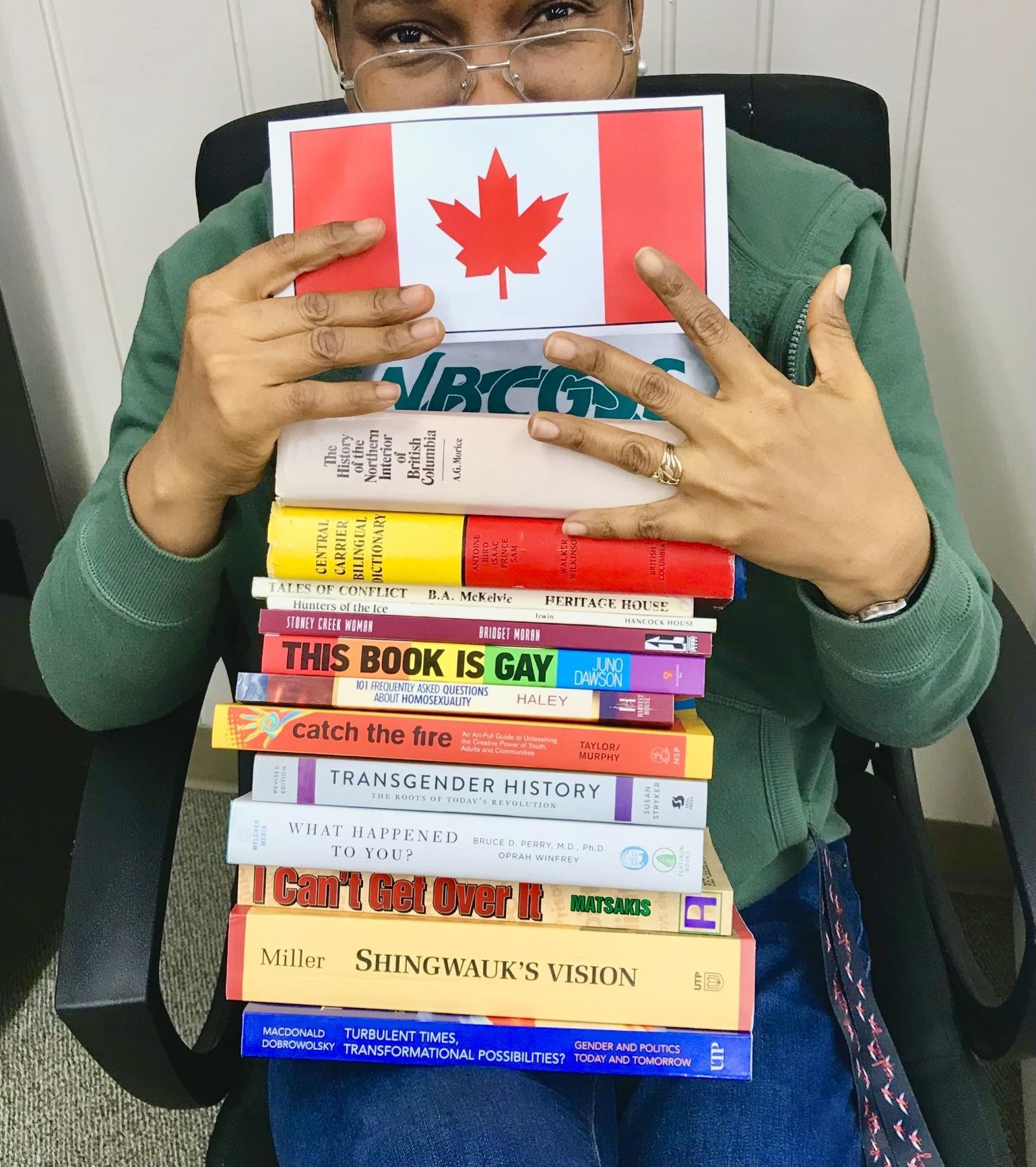

Being an international student was the best option for me financially, my career and my children. I have read many books on the individual and collective struggles of other feminists from different parts of the world and in diverse sectors. Knowledge is power, and within my search and quest for more information, I can participate in a healthier socio-economic structure for me as a feminist and a woman. My circumstance adequately describes this second concept by Alexandra Dobrowolsky's "A Diverse, Feminist, Open Door Canada? Trudeau-Styled Equality Liberalisms and Feminisms". Here, the author described rollback neoliberalism where those with money, skills, qualifications, and official language capacity indicate an ideal migrant. She further explains that, consequently, immigration policies came to favour economic immigrant selection as immigration became viewed for its potential profits for attaining economic and political leverage. However, I agree with the author because I couldn't afford to come into Canada as an economic migrant due to insufficient funds. It would take me a more protracted, demanding, enduring, still yet rewarding route as an international female graduate student of gender studies in becoming a permanent resident, a feminist and a women advocate in the best possible way.